Orchestra Hall in Detroit recently celebrated its 100th birthday, and local architectural history guru Benjamin Gravel posted several historic photos of it from the Library of Congress that were taken when the hall was abandoned. I had seen the photos before, but it gave me the idea to reuse them here to do a sort of simulated explore of the building as if we could step back in time to 1970 when it was abandoned. This year, 2019, also signifies the 30th anniversary of the reopening of Orchestra Hall after its long dereliction.

A documentary on Detroit Public Television is even being made about Orchestra Hall, and there is also a new book out by Mark Stryker (which I received through my fundraiser donation to our local classical station, WRCJ).

I grew up listening to classical music on the old WQRS in the backseat of my dad's car (when he wasn't rocking out to WLLZ). I remember Orchestra Hall's triumphant reopening in 1989, since at that time I was just starting orchestra class in 5th grade. I played the viola (slightly bigger than a violin), and I was infatuated back then with Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart. I stayed in orchestra class all the way through high school, where our group competed regularly, even out of state. Playing music was one of the very few things about school that I enjoyed, and I remember going to see the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (DSO) in this building on class field trips. As an even younger child I remember seeing the DSO perform at Ford Auditorium while Orchestra Hall still lay abandoned.

I grew up listening to classical music on the old WQRS in the backseat of my dad's car (when he wasn't rocking out to WLLZ). I remember Orchestra Hall's triumphant reopening in 1989, since at that time I was just starting orchestra class in 5th grade. I played the viola (slightly bigger than a violin), and I was infatuated back then with Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart. I stayed in orchestra class all the way through high school, where our group competed regularly, even out of state. Playing music was one of the very few things about school that I enjoyed, and I remember going to see the Detroit Symphony Orchestra (DSO) in this building on class field trips. As an even younger child I remember seeing the DSO perform at Ford Auditorium while Orchestra Hall still lay abandoned.

Orchestra Hall was built in 1919, and has served for decades as home to the fourth-oldest symphony orchestra in North America. It also represents one of the most important African-American musical venues in Detroit history, since from 1941 to 1951 it was known as the legendary "Paradise Theater," hosting many famous jazz acts. It was our Apollo.

The Detroit Symphony Orchestra itself was first founded in 1887, and originally played in the old opera house that once stood on Campus Martius.

The Detroit Symphony Orchestra itself was first founded in 1887, and originally played in the old opera house that once stood on Campus Martius.

|

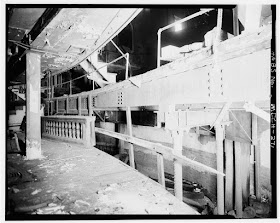

| Image from Historic American Building Survey, by Allen Stross |

"The dark and clammy interior of Orchestra Hall looks like a set for the last, eerie act of a play about the downfall of Detroit." The article from 1970 entitled "Bach Violin Music Tries to Reawaken Old Orchestra Hall" goes on to describe the pigeons, burned seats, and fallen plaster made damp by the rain coming through the roof. Amidst all this decay the sound of a violin pierced through the darkness, as the DSO's assistant concertmaster played alone on the crumbling stage.

Paul Ganson, DSO bassoonist, stood next to a fallen chandelier talking to the Free Press reporter about plans to revive the old hall, and its famous acoustics. Even with much of the ceiling damaged, that "rare and mysterious" acoustic quality was apparently still alive in there somewhere, as the sound of Bach echoing through the ruins seemed to reveal.

The feeble strains being played were a far cry from the heydays when the full orchestra was in here filling the huge room with their warm sound, but Ganson was dedicated to bringing that back. Vagrants and vandals now inhabited the darkened hall, allegedly "crawling in through the sewers." There was also a film crew in here shooting a short movie to hopefully help raise money for the effort to buy and restore the building. They needed at least a million dollars, and hadn't yet raised anything.

[I want to pause here for a moment to admit that in 2006 when I first read this old article, I was so inspired by the thought of a rogue musician sneaking into the old hall to play alone on the darkened stage that I myself snuck into the old Michigan Central train station with my viola to play a few licks at night in the crazy acoustics of the domed waiting room.]

Here is Paul Ganson playing his bassoon on the roof during reconstruction six years later; he is widely credited as the man who started the "Save Orchestra Hall" campaign:

Local historian and activist Jamon Jordan reminds us that there’s more to the story, however; as with so many of Detroit's historic landmarks, it has both a "white history" and a "black history." Around the same time Save Orchestra Hall got started, a similar group, "Save Paradise Theater," was founded in Detroit's black community to organize benefit concerts at the hall to fundraise for its restoration. Without the partnership of these two groups, the project might never have succeeded, and Orchestra Hall could have been demolished.

Jordan outlines the history of Orchestra Hall during its Paradise Theater days, noting that it had only been open sporadically between 1940-1941 as the Town Theater (a burlesque), before being seized for back taxes. The city planned to demolish the building and redevelop the site, but wealthy black businessmen Andrew "Jap" Sneed, Everett Watson, John Roxborough, and Irving Roane approached the city to buy it. However, black people (even wealthy ones) were not allowed to buy property on Woodward Avenue, Detroit's main throughfare, particularly on the west side of the street.

Jordan says that two Jewish businessmen, brothers Ben and Lou Cohen, bought the building and agreed to a long-term lease with the African-American businessmen mentioned above. They turned it into the Paradise Theater. Since the Graystone Ballroom, Detroit's preeminent—yet segregated—jazz venue was only open to blacks on Mondays, I imagine that the opening of the Paradise just a few blocks south of there was a highly celebrated move in the black community.

Named after Paradise Valley, Detroit's historic black business and entertainment district, it hosted great musicians and performers like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Dizzie Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Aretha Franklin, and Ella Fitzgerald. My colleague Benjamin Gravel asserted that the Paradise was Lena Horne's favorite venue to perform at, since it was the only one where she did not need to use a microphone due to its superior acoustics. Historian Mark Stryker (and others) boast that Orchestra Hall is on par with the greatest concert halls in the world known for their acoustics: Vienna's Musikverein, the Conzertgebouw in Amsterdam, and Boston's Symphony Hall.

I imagine there are very few stages in the world that can claim to have had musical idols the likes of both Sergei Rachmaninoff and Ella Fitzgerald stand upon them; this one can. By the way, the woman handling the marquis in this next photo was the niece of famous Detroit boxer Joe Louis:

As the big band era was drawing to an end the Paradise Theater waned, closing its doors in 1951. Ironically the 1950s-1960s saw Detroit enter its heyday as an influential center of the jazz genre, but the trend was turning back to smaller jazz ensembles and smaller, more intimate lounges. The Paradise was a little too big, and stage shows seemed old fashioned; Detroit was into bebop now. According to Jordan African-Americans were freer to own some properties on Woodward by that time, and soon after the Paradise Theater closed the building was bought again by Rev. James Lofton and the Church of Our Prayer. The choir, led by Charles Craig, recorded historic gospel classics there. Craig was later known for partnering with Rev. James Cleveland, who made his mark in Detroit as the "King of Gospel."

The building remained closed through the 1960s, while DSO musicians recorded with the Funk Brothers on some of Motown's greatest hits. In 1970, Gino's Restaurant Company bought the building and began to demolish it to put in a cafeteria, but that was when the Save Orchestra Hall and Save Paradise Theater groups were formed and began fighting to save it. Today, Orchestra Hall hosts the "Paradise Jazz Series" in honor of the history of its time as the Paradise Theater, according to Jamon Jordan. Who knows whatever happened to that fabulous "PARADISE" neon marquis seen above; I'm sure it's been recycled into Toyotas by now.

Paul Ganson, DSO bassoonist, stood next to a fallen chandelier talking to the Free Press reporter about plans to revive the old hall, and its famous acoustics. Even with much of the ceiling damaged, that "rare and mysterious" acoustic quality was apparently still alive in there somewhere, as the sound of Bach echoing through the ruins seemed to reveal.

|

| Image by Joe Lippincott, via Detroit Free Press |

[I want to pause here for a moment to admit that in 2006 when I first read this old article, I was so inspired by the thought of a rogue musician sneaking into the old hall to play alone on the darkened stage that I myself snuck into the old Michigan Central train station with my viola to play a few licks at night in the crazy acoustics of the domed waiting room.]

Here is Paul Ganson playing his bassoon on the roof during reconstruction six years later; he is widely credited as the man who started the "Save Orchestra Hall" campaign:

|

| Image from archives of Paul Ganson, c.1976 |

Jordan outlines the history of Orchestra Hall during its Paradise Theater days, noting that it had only been open sporadically between 1940-1941 as the Town Theater (a burlesque), before being seized for back taxes. The city planned to demolish the building and redevelop the site, but wealthy black businessmen Andrew "Jap" Sneed, Everett Watson, John Roxborough, and Irving Roane approached the city to buy it. However, black people (even wealthy ones) were not allowed to buy property on Woodward Avenue, Detroit's main throughfare, particularly on the west side of the street.

Jordan says that two Jewish businessmen, brothers Ben and Lou Cohen, bought the building and agreed to a long-term lease with the African-American businessmen mentioned above. They turned it into the Paradise Theater. Since the Graystone Ballroom, Detroit's preeminent—yet segregated—jazz venue was only open to blacks on Mondays, I imagine that the opening of the Paradise just a few blocks south of there was a highly celebrated move in the black community.

Named after Paradise Valley, Detroit's historic black business and entertainment district, it hosted great musicians and performers like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Dizzie Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Aretha Franklin, and Ella Fitzgerald. My colleague Benjamin Gravel asserted that the Paradise was Lena Horne's favorite venue to perform at, since it was the only one where she did not need to use a microphone due to its superior acoustics. Historian Mark Stryker (and others) boast that Orchestra Hall is on par with the greatest concert halls in the world known for their acoustics: Vienna's Musikverein, the Conzertgebouw in Amsterdam, and Boston's Symphony Hall.

|

| Image from Historic American Building Survey, by Allen Stross |

|

| Image via dso.org |

The building remained closed through the 1960s, while DSO musicians recorded with the Funk Brothers on some of Motown's greatest hits. In 1970, Gino's Restaurant Company bought the building and began to demolish it to put in a cafeteria, but that was when the Save Orchestra Hall and Save Paradise Theater groups were formed and began fighting to save it. Today, Orchestra Hall hosts the "Paradise Jazz Series" in honor of the history of its time as the Paradise Theater, according to Jamon Jordan. Who knows whatever happened to that fabulous "PARADISE" neon marquis seen above; I'm sure it's been recycled into Toyotas by now.

|

| Image from Historic American Building Survey, by Allen Stross |

Gales left in 1917 to be succeeded by a famous Russian pianist who would lead the DSO into its golden era: the tall, wild-haired Ossip Gabrilowitsch. He was coming fresh off of a tour with the Boston Symphony, and was good friends with famous composers Gustav Mahler and Sergei Rachmaninoff, not to mention he was Mark Twain's son-in-law. Gabrilowitsch "brought instant credibility to the DSO."

Detroit author Richard Bak writes that "at least part of" Ossip's fame derived directly from this marriage to Mark Twain's daughter, Clara Clemens. He was studying piano in Vienna when the two met. They moved to Detroit in 1918, taking up residence at 611 West Boston Street. Bak goes on to say that Clara would "occasionally sing and act in local theater groups" but that her professional performing days were over. I imagine that Ossip and Clara were probably among the most talked-about couples in Detroit's high society.

|

| Image from Historic American Building Survey, by Allen Stross |

Under Gabrilowitsch's baton, the DSO rose in the 1920s to become one of the most prominent orchestras in North America, performing with guest artists such as Enrico Caruso, Igor Stravinsky, Richard Strauss, Marian Anderson, Sergei Rachmaninoff, George Gershwin, Isadora Duncan, Anna Pavlova, Jascha Heifetz, Pablo Casals, etc. In 1922, Ossip Gabrilowitsch led the orchestra and guest pianist Artur Schnabel in the world's first radio broadcast of a symphonic concert, on WWJ-AM. The DSO performed at Carnegie Hall for the first time in 1928 and made their first recording there. There was even a pipe organ installed at Orchestra Hall in 1924, dedicated by the great Marcel Dupré.

|

| Image from Historic American Building Survey, by Allen Stross |

The DSO distinguished themselves in 1934 however, becoming the nation's first official radio broadcast orchestra, performing for millions of Americans over the airwaves on the Ford Symphony Hour national radio show. I imagine this is sort of like how the Detroit Lions managed to become the official nationally broadcast football team every year on Thanksgiving, which interestingly enough also happened in 1934.

With the onset of World War II and the draft, the DSO disbanded again in 1942 (for the fourth time, if you're counting). Orchestra patron Henry Reichhold resurrected the DSO in 1944 and installed Karl Krueger as music director. But while the war was raging, Orchestra Hall had been sitting vacant, and reopened in 1941 as the Paradise Theater. So the DSO's new home became the Music Hall, on Madison Street. The DSO soon moved again, to the Masonic Temple, where they had to share facilities with other programs. Internal strife caused a fifth disbanding of the orchestra, in 1949.

|

| Image by Joe Lippincott, via Detroit Free Press |

But because it was in poor shape, the DSO instead performed during the Paray years at the Masonic Temple, until 1956 when they moved into their new riverfront home, Ford Auditorium (named after Henry and Edsel Ford, whose family donated $1 million to its construction). Despite its crappy acoustics and austere modern architecture, Ford Auditorium remained their official home for 33 years (again, like the Detroit Lions, being owned by the family of Henry Ford is not really a recipe for success).

|

| Image from Historic American Building Survey, by Allen Stross |

During the restoration years there were many recordings and benefit concerts held there by the DSO, the Classical Roots Series, and the Chamber Music Society of Detroit. The atmosphere in those days was a little "underground" (I imagine sort of like seeing a heavy metal show at Harpo's), since the hall was still in rough condition. By 1989 the DSO was finally able to return home to Orchestra Hall after being gone for 50 years. It cost $7 million and took 19 years, but the restoration was worth it. Interestingly, the move back was considered a little risky, since the DSO's mainly suburban audience saw Woodward as "a scary neighborhood" back then, and the orchestra itself was fighting off bankruptcy. When you think about it, of all the Detroit institutions that could or would have fled to the suburbs during city's declining years, the DSO seems like a natural candidate—but they stayed.

The 1990s were defined by the appointment of Neeme Järvi as music director, which signified another new era of reinvigorated performance and commitment to the city. In 1997 the DSO built a speculative office building across the street called Orchestra Place, which increased their revenue. The Max M. and Marjorie S. Fisher Music Center was built onto Orchestra Hall in 2003, an expansion that included new performance and educational space, as well as administrative offices.

Leonard Slatkin was appointed maestro in 2008 to much acclaim, although Detroit was spiraling into recession. I still have a 2010-2011 concert calendar, which lists all of the performances that never occurred due to the bitter strike that year. The musicians walked out of contract talks in response to management demands for a 33% wage cut, and other regressive changes. But under Slatkin the DSO managed to resolve the strike, lower ticket prices, and introduce new innovative programming designed to bring more young people into contact with classical concerts. According to detroithistorical.org. the "Live From Orchestra Hall" series offers free, live webcasts to fans worldwide as the first (and only) initiative of its type among major orchestras, making it "a point of inspiration for the future of arts accessibility." Better yet, the hall's old pipe organ that had been moved to Calvary Presbyterian Church (and later ended up in Traverse City) was bought back by the DSO in 2011, but it remains in storage, according to Mark Stryker.

|

| Image from Historic American Building Survey, by Allen Stross |

This is why I sneer when I hear some developer (like the Ilitches) telling us that a building is "too far gone" and "can't be saved." If a bunch of average people with day jobs can manage to accomplish restoring a massive icon like Orchestra Hall, then I'll be damned if I believe a billionaire telling me he can't, or won't. He just wants to pave paradise and put up a parking lot...but no one visits a city to look at parking lots. Detroit needs real mass transit, so that we don't need parking lots...but that's a whole 'nother story.

References:

Destiny: 100 Years of Music, Magic, and Community at Orchestra Hall in Detroit, by Mark Stryker

"Bach Violin Music Tries to Reawaken Old Orchestra Hall," Detroit Free Press, October 23, 1970, p. 10-D

http://www.dptv.org/specials/orchestra-hall-100/

https://www.freep.com/story/entertainment/music/2019/10/03/detroit-symphony-orchestra-hall-100th-anniversary/3835721002/

https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/detroit-opera-house

https://www.dso.org/about-the-dso/our-history/orchestra-hall/

https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Bio/DSO.htm

Boneyards: Detroit Under Ground, by Richard Bak, p. 49