Now, besides the creation of the automobile industry and the multitude of subsequent developments that sprang from it, Detroit has undeniably shaped the course of human history in 14 main ways:

[1] by the invention of the first practical home refrigerator unit (Kelvinator)[2] by the creation of the first industrial pharmaceutical laboratory, and revolutionizing the production of medicine (Parke-Davis, R.P. Scherer)[3] by redefining the way we produce, perform, and enjoy music (Motown, Grande Ballroom, Detroit Techno)[4] by redefining the way we use film as a promotional medium (Jam Handy Studios)[5] by pioneering concepts in radio broadcasting, like regularly scheduled news reports and play-by-play sports coverage (950 WWJ)[6] by initiating the first public works / work-relief programs (Mayor Hazen Pingree)[7] by pioneering the use of radio for mobile dispatch (Detroit Police Dept.)[8] by inaugurating the first airline service and modern airport (Henry Ford)[9] by introducing modern reinforced concrete architecture (Albert Kahn)[10] by pioneering several major breakthroughs in watercraft design and hydraulics (Gar Wood, Dick Hill, Cameron Waterman, John Hacker)[11] by developing the first practical coin-operated machines (Auguste Caille)[12] by demonstrating the first electric-powered railway (Charles Van DePoele)[13] by introducing breakthroughs in computing, as well as the revolutionary Norden bomb sight (Burroughs Corporation)[14] by reshaping retail theory, consumer habits, and urban development with the construction of the first suburban mall (Victor Gruen, Northland Center)

But there is one more thing that a Detroiter did that changed the course of history, and that was to revolutionize the meatpacking and produce industries by popularizing the concept of refrigerated freight shipment...

The name George H. Hammond does not readily conjure up mental images of some famous product, like that of Henry Ford, the Dodge Brothers, or even Charles Kettering, but Hammond once commanded an empire that stretched across the breadth of this nation, his name was on the side of almost every train, a large city in Indiana is named after him, and Michigan's first skyscraper was even built in his honor, but today this unremarkable pile of brick here is basically the only thing left to prove this legendary Detroiter ever existed...

George Hammond was a meatpacker. Although he is often credited with inventing refrigerated rail transport, it would be more correct to say that he was the one who pioneered means to make it practical, and who was the one most instrumental in popularizing it. Which is what we Detroiters do—we don't actually invent things—we perfect them, or invent new ways to use them that no one thought of before. You can see this from my 14-point list, above.

Without him, it would've been a lot harder to get decent meat or produce in much of this country without paying rich man's prices. Thus it could be said that Hammond was largely responsible for bringing things like steak and fresh fruit out of the realm of rare indulgence, and into the common American diet during Victorian times.

This building was once part of a larger complex of buildings that made up the old Hammond, Standish & Co. meatpacking plant. You may recall that I wrote about the meatpacking business in Detroit in an older post, exploring the Thorn Apple Valley Slaughterhouse in Eastern Market.

By the 1920s, this was a robust complex of buildings densely nestled together atop the Michigan Central Railroad's many sidings and spurs that sat behind the big iconic train station between Corktown and Mexicantown. Perusing the many labels that the c.1921 Sanborn map used to identify the buildings that used to stand here, I see "hog coolers," "cattle pens," "dry salt rooms," "cattle runway," "pork curing," "packing & shipping," "hanging," "rendering," "cooper shop," "coal bunkers," "refrigerating & cutting," "ice machines," "freezing tanks," "sausage manufacturing," "wholesale market," "lunch room," "retail market," and "offices."

This particular building is actually two stuck together, labelled Building #9 and #10 on the Sanborn map, built in 1911 and 1916, respectively. The rest of the buildings were also of mixed wood-post and reinforced concrete construction, all of them built before 1918. The newer building was labeled as containing the "lard refining room," "cooper shop," and "beef coolers." The older building was labeled as "fertilizer building," "rendering building," and "abattoir." What is an abattoir, you ask? Well, it's a fancy French word for a place where frightened animals are decapitated and ground into a paste that you will eventually cook and put in your mouth. Perhaps this Jam Handy-style educational film will help explain: "Meat and You"

For five hours "it burned stubbornly in the night, a five-alarm fire that danced elusively, like a ghost through the old abandoned building" on the night of November 27, 1965, a Free Press article recounted, "before 120 firemen put it to rest as it kept hissing in protest before the dawn when ghosts must sleep." That was the night this complex was reduced to the one remaining building you see here. Ironically, the Detroit Historical Museum was also running an exhibit on the life of Mr. Hammond at the time of the fire.

Mr. Hammond was born in Fitchburg, Massachusetts in 1838, and at a very young age "went to work in that bleak New England factory town," in a small shop where 12-year-old girls made hats and mattresses for pennies. Hammond was such an astute employee that he took up the business at age 15, upon his employer's retirement.

After six months of that he sold it all to come to Detroit at the behest of a friend, in 1854. He then opened a hat and mattress factory here, but after only a few years it was destroyed by fire, leaving him nearly destitute. "Fire appears like a red thread on the fabric of Hammond's story," the Free Press reporter foreshadowed.

In 1857 Hammond re-established himself manufacturing chairs at the corner of State & Farmer, but so far Detroit wasn't working out so well for him, because six months later the building burned. With what little money he had left, Hammond got a loan and went into a totally new business, opening a small meat shop at the corner of Howard Street and Third.

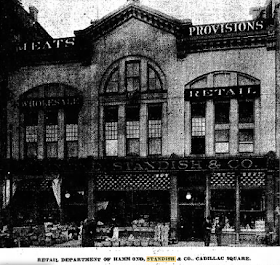

The prosperity that came to Detroit following the Civil War (and those who survived it) enabled Hammond to expand his business into a bigger store at 38 Michigan Grand Avenue, which is what Cadillac Square used to be called. Apparently the Civil War had taught him a thing or two about butchery, so he began slaughtering his own cattle here on 20th Street, and sold meat wholesale as well as retail. There was another fire in May 1883, nearly destroying his shop at Cadillac Square & Bates, but he was financially in a much better position to recover by that point.

In 1885 Hammond suffered yet another major fire, when this slaughterhouse on 20th Street burned down. And you thought Katoi was having a rough go. This next photo shows the original plant that stood here before the fire...the buildings that stand on this site today were built to replace what was lost:

Mr. Hammond's first brush with the idea of refrigerated railroad cars came when he met William Davis.

Mr. Davis was a fish merchant who claimed some level of engineering ability and happened to have a market stall next to Hammond's. He had been interested in refrigeration for some time, since he had his fish brought in all the way from Lake Superior, and in fact he'd already designed stationary refrigerators for himself and a couple friends in the fruit business. Hammond provided the financing, and had Davis engineer him a refrigerated boxcar, known to railroaders as "reefer" cars for short. In 1868 Davis was granted U.S. Patent #78932 for his reefer car—and then promptly died that same year. Hammond bought the patent rights from Davis's heirs, and the first Hammond-Davis reefer was built the following April at the Michigan Car Co. Works of Detroit. Hammond risked a shipment of 16,000lbs of beef to Boston, and it arrived there in May 1869, allegedly in a more appealing condition than the beef which—according to the local papers—could be found in Boston's own meat markets. Thus, a new industry was born, driven by a newfound demand.

By the way, I wrote a lot about Michigan's connection to the history of refrigeration technology in other posts on this website:

The "Cathedral of Refrigeration"

Lambs to the Slaughter

How Detroit and the Yoopee Used to be Connected

Acme Jackson

Arctic Ice Cream

Anyway, even though there were primitive reefer cars in service as early as the 1840s, many of them were poorly designed. The first patent ever granted for a refrigerated boxcar was actually issued to a Detroiter named John B. Sutherland, in November 1867, several months before the Hammond-Davis design. Sutherland was the master car builder of the Michigan Central Railroad at the time, and also had an earlier patent regarding sleeper cars. He lived at the corner of 10th & Woodbridge (roughly where West Riverfront Park is today), and was one of the original trustees of the Wayne County Savings Bank.

According to the book All Our Yesterdays, A Brief History of Detroit by Frank and Arthur Woodford, before Detroit became the Motor City it was already well known as a railcar manufacturing center after the Civil War. Even though it was not invented in Detroit, the famous Pullman sleeper car was manufactured here from 1871 to 1893, and along with Sutherland's and Davis's work on the refrigerator car, other innovations in railroading were inspired, including the snow plow and the track cleaner, both invented in Detroit by Augustus Day.

According to the book The American Railroad Freight Car by John H. White, the Hammond-Davis reefer cost $2,000 each to build, leading White to call it "as expensive as it was impractical." It was not successful as a year-round meat carrier he wrote, since in warm weather dressed beef would occasionally arrive spoiled. Also, since the carcasses were suspended from the ceiling of the car they tended to shift when the train entered a curve, causing a few derailments. A fruit dealer named Parker Earle had tried a Hammond-Davis reefer for a shipment of strawberries but found it to yield poor results, since the berries closest to the brine tanks were damaged by frost and could not be sold. Another load of fruit was sent to California in late 1870, with better results. Despite these faults, the Hammond-Davis design was greatly improved in the 1880s, and the cars stayed in use for quite a while longer.

Prior to Davis's design, "refrigerated" railcars were merely boxcars packed with ice blocks—and they required 11 tons of it—making shipping dressed beef unfeasible without constantly re-icing the railcars. However, shipping live animals long-distance was also inefficient because they would lose weight and quality during the trip. Livestock needed to be fed during long trips, and their manure disposed of afterward. But shipping dressed beef as opposed to the whole animal represented a 60% weight reduction—which in turn represented a 60% increase in profits for men like Hammond. The practical reefer car was the key to all these problems—and with Davis's patented brine circulation system, only 2,500lbs of ice was needed. Although the Davis reefer did have its flaws, this was the development Hammond needed to start a revolution in the transport of perishable goods.

The only hangup was the fact that the railroads made their money from shipping more weight, not less, so they balked at Hammond's overtures of building reefer cars to ship dressed meat. Since the big railroads running through Chicago were major shareholders in the great Union Stock Yards there, they were reluctant to do anything that would hurt their own business. The railroads were invested heavily in stockyards, feedlots, and thousands of cattle hauling cars that were not adaptable to any other purpose. Just when they had everything set up perfectly White writes, a group of meatpacking firms led by Hammond "wanted to ruin everything" by shipping dressed beef to the big Eastern cities. Those that united behind Hammond included Swift, Cudahy, and Armour—his main competitors—yet they joined him in his fight against the big railroads.

The railroads responded by doing what came naturally—they raised their rates on shipping dressed meat, and would refuse to supply or run reefer cars. So the Midwestern meatpackers turned to Michigan and the Grand Trunk Railroad, which passed through Canada and was not financially beholden to the Union Stock Yards, and they purchased their own cars. Hammond-Standish already shipped through Canada via the Michigan Central Railroad.

White says that the idea of shipper lines originated with the meatpackers of the Midwest. Hammond originally worked with the Blue Line, but later decided to operate his own line. By 1885 he had 600 reefer cars in service, and by the year 1900 that number had doubled. Other western meatpackers soon saw the potential profit in shipping dressed beef to the population centers of the East Coast, and subsequently Swift, Cudahy, and other big names started their own shipper lines.

There was more than a little resentment of the railroad industry in those days, which was seen by the common man as a corporate juggernaut owned by tycoon monopolists like Vanderbilt and J.P. Morgan, who constantly jacked up rates at will on a captive market. It was this very resentment of the railroad that in large part fed directly into the appeal of the Detroit automobile industry once the Motor City got going building cars. The automobile was advertised as a symbol of freedom—not just freedom from being confined to rails, but freedom from being forced to pay the fat-cat railroad tycoons to use them. It was this same sentiment that led to the dissolution of the Detroit street rail system, but that is another story. Funny how the bran-new Q-Line everyone is suddenly excited about is also controlled by a fat-cat tycoon today (ahem, Dan Gilbert)...okay I'll shut up now.

But the connections between the meatpacking and railroad industries and the Detroit automobile industry go even deeper than that. It is well known that Henry Ford himself took his inspiration for the moving assembly line from the methods used in slaughterhouses. A historic photo at thehenryford.org depicts a conveyor at Swift & Co. in Chicago, moving hog carcasses past the men who did the meat cutting. The photo's caption reads,

By 1873 Hammond-Standish was making $1 million per year, and by 1875 it was $2 million. They set up plants and warehouses in Boston, Omaha, Indiana, New York, and even Chicago itself—the heart of "The Jungle." The town of Hammond, named after Mr. Hammond himself, grew to become Indiana's sixth largest city. He even began shipping beef to Europe! According to The History of Wayne County by Clarence M. Burton, Hammond was the first to send reefer cars across the ocean. One article says he invented a refrigeration room for seagoing ships, successfully delivering his first consignment of dressed beef in 1879 to Liverpool, England.

By this point in the story you may be wondering where the "Standish" part of the company name comes from. James Darrow Standish was one of the organizers of Hammond Standish & Co. in 1872 along with Sidney B. Dixon. They incorporated in 1880. Standish was its secretary and treasurer from its inception to its demise...other than that, I haven't found much reference to Mr. Standish or his involvement in the company, since most of the news articles focus on Mr. Hammond. Mr. Dixon held the position of company vice president.

Historian Clarence M. Burton writes that like Hammond, the Standishes also originated from out east, and even trace their lineage back to Captain Myles Standish of the Mayflower (George Hammond was descended from William Penn's sister). The Standishes were one of the pioneer families of Michigan, settling in Pontiac before coming to Detroit. One of them later married into the Stroh family, of Detroit beer-brewing prestige. The Standish family home was at 1411 Burns Avenue in Detroit's prestigious Indian Village, and J.D. was a member of the Detroit Athletic Club as well as several other clubs.

In 1881 Mr. Standish held the post of secretary and treasurer at the G.H. Hammond Co. (a branch of the parent company, I presume), which moved its general offices to Chicago in 1889, and subsequently merged in 1902 with the National Packing Co. (aka, the "Beef Trust," which was broken up by the Supreme Court in 1905). In 1904 he returned to Detroit to become secretary of Hammond-Standish again. A Free Press article in October 1905 indicated that C.F. Hammond, J.D. Standish, S.B. Dixon were all still the executive officers of the company. Burton also lists a Charles Dana Standish, perhaps an older brother, as being a partner in Hammond-Standish, who from 1893 to 1900 also helped establish the J.H. Hammond Co., which was the branch of the company that was based in Indiana on the edge of metropolitan Chicago. The town subsequently named itself Hammond.

Standish Street (which runs in front of this building) was actually named Hammond up until sometime between 1884 and 1897 (according to the Sanborn maps). Why the name was changed I have no idea, but it is interesting to note that the name change might have occurred shortly after the death of George Hammond in 1886...maybe there had been some jealous rivalry between the two business partners?

The c.1884 Sanborn map of Detroit shows the old original complex from the 1860s still standing here (which burned down one year later), and the residential neighborhood in this area was already fully developed. There was a planing mill labeled "Diamond Match Co." across the street from this building, on the corner of 21st where Hammond's truck garages would later sit. Nearby was the Detroit Bridge & Iron Works, Stephen Pratts Boiler Works, various coal and lumber yards, "Williard Clark & Co. Pork Packing" was across the railyard from this building. Also of note in the area, the Detroit Soap Works was shown at the corner of what would later become Vernor and 25th, although in 1884, 25th Street was the city limits. I wonder if they got their tallow from Hammond.

The c.1897 Sanborn map shows the new complex starting to take shape on this site. "Parker, Webb & Co. Pork Packers," and "Caplis & Cross, Beef Slaughterers" were now located just north of the Michigan Central railyard, on 20th Street where Williard Clark & Co. had been on the 1884 map.

By 1886 Hammond was slaughtering 2,000 head of cattle and producing 50,000lbs of oleomargarine per day, and annual sales hit $15 million; they also had distribution warehouses in East Saginaw, Bay City, and Mackinaw. That winter Mr. Hammond suddenly perished of an apparent heart attack at his Victorian mansion at 105 Howard Street. He was only 48 years old...too much cholesterol in his meaty diet I guess. This next photo shows Mr. Hammond's home, which was apparently built on the same site as that first meat shop he ever opened, way back in 1857:

Weeks before Mr. Hammond passed, there was also another fire at this plant on 20th Street in 1886. The damage was repaired and the complex was subsequently expanded to be bigger than ever before. A different Free Press article from December 1886 said that Hammond was currently building the largest oleomargarine factory in the world (probably in response to the last fire), to have an alleged output of 100,000lbs per day—twice as much as before.

Construction on it had been stalled since "the labor troubles last summer," the article noted, but claimed that with the death of its founder the business "was headed for its doom." In 1890 Hammond-Standish was sold to a British company according to the Free Press, later absorbing the Armour Meat Co., but it would seem that at least the Detroit part of the business nonetheless lived on under the Hammond name until the 1950s.

Mr. Hammond left behind his wife Ellen Barry, and eight children, as well as the largest family real estate holdings in Detroit, and an estate worth $5 million. He was described in one article as an "unostentatious" philanthropist, and is enshrined in Detroit's historic Elmwood Cemetery. Of the eight heirs to the Hammond legacy, sons George, Charles, Edward, and daughter Florence went into the family business. Charles F. Hammond became president and treasurer of the meat business, while Edward was president of the Hammond Building Company and Florence served as its secretary and treasurer, according to the Detroit Public Library.

When George Hammond died, he had just begun work on a fabulous new landmark office building downtown. A site had been cleared, but nothing had been built yet. Chicago architect Harry W.J. Edbrooke was able to persuade Mrs. Hammond to hire him to finish the planned skyscraper in her husband's memory.

According to historian Robert Conot, when the Hammond Building opened in 1890 a state holiday was declared, and people came from hundreds of miles around to see the marvelous new tower. Bands played, speeches were made, fireworks were launched, and a tightrope walker awed the crowd by traversing a cable strung from the belltower of Old City Hall to the roof of the new skyscraper. According to detroithistorical.org, it was one of the largest masonry buildings ever constructed in the United States at that time.

According to a history of Detroit by Frank and Arthur Woodford, the site at Fort Street & Griswold where the Hammond Building was erected has a fascinating history of its own. It was previously the homesite of James Abbott, one of Detroit's first postmasters, whose wife was Sarah Whistler, aunt to the famous American painter James McNeill Whistler—who was said to have visited the Abbott home often during his boyhood. His grandfather, Captain John Whistler, was stationed in Detroit during the War of 1812.

As an artist in his prime, James McNeill Whistler painted the famously controversial Peacock Room, which was later installed in the landmark Detroit mansion of Charles Lang Freer, at 71 East Ferry Avenue. Mr. Freer was an industrialist and an art patron, who just so happened to have been co-founder of Detroit's Peninsular Car Co., which built the reefer cars that improved on the Hammond-Davis design for Swift & Co.—how's that for six degrees of separation?

For all of their to-do about the railroad, by 1920 Hammond-Standish had almost nothing to do with it, having converted all of its shipping to be done by motor truck instead. Hammond both led the way to, and away from the idea of shipping meat by rail. An article in the trade journal The Commercial Vehicle bragged that Hammond-Standish was able to reach customers 30 miles away without use of the railroads, and furthermore deliveries within that range were completed two or three times quicker than by rail. The article cited high rail freight rates and hub warehousing cold storage costs needed to prevent spoilage during shipment—all of which were eliminated when shipping by motor truck.

When Hammond started out in the 1850s, it was with 40 horses and wagons, limiting sales to local demand. The outside business gained from the increased range of motor truck delivery more than doubled the company's sales.

In 1920 Hammond operated five Ford light delivery trucks, five 2-ton and seven 3.5-ton Federal Motor Trucks, and one 4-ton Packard truck. With the trucks it was possible for one driver to take on two or more routes per day, whereas in the days of horses he could only complete one route per day. This stony-faced, barrel-chested Corktown Irishman was apparently the lug in charge of Hammond's truck fleet in the 1920s:

Polk's City Directory for 1921 shows Hammond-Standish owning several other buildings in the city, at 2424 Riopelle in Eastern Market, at 8504 Jos. Campau in Hamtramck, at 7871 W. Jefferson in Delray, and at the corner of 18th & Perry near Western Market. The 1940 Polk's lists another location at 1549 Division in Eastern Market (now Jimmy's Quality Meats), which is the only one of these buildings still standing today.

On the south side of Standish Street from this building in 1921 were rows and rows of frame houses, a small bowling alley, as well as the Schulte Soap Co. (manufacturers of tallow, according to Sanborn maps). Small wonder they would be located across from a slaughterhouse. At the corner of 21st there was also another smaller ancillary complex of Hammond-owned buildings, labelled as garages for the company's delivery trucks, supply storage, and "hair cleaning works." I presume that this meant Hammond-Standish was also in the business of selling the hair shorn from their cattle, which was being used for upholstery purposes by the Detroit automobile industry at that time.

In the immediate surroundings of this building, other industries that were shown on the c.1921 map included the F.J. Hasty & Sons Cooperage Works next-door (making wooden barrels and casks), and next to them was the Griffin Wheel Co. foundry, makers of car wheels and other chilled castings for the railroad industry.

This was the building that faced the railroad spurs, and had open shipping docks all along its western side for loading the meat onto the trains for shipment. The rails were ripped out long ago, and the docks were converted for truck shipment.

The 1940 Polk's city directory contained a detailed writeup on the Hammond-Standish Co., which was transcribed on the atdetroit.net forum by user "Mikem." The directory said that the Detroit packing industry had suffered from a loss of "the national fame it deserves" due to the overwhelming focus on the city's auto industry, and that when meatpacking is mentioned, cities like Chicago and Kansas City came to mind instead.

Detroit was then estimated to be fourth in the nation for meatpacking business, and was one of the few cities killing enough livestock to provide for its own needs without importing. Detroit was still doing quite a healthy meat export business as well, and Polk's mentioned that when the St. Lawrence Seaway project was completed the meatpackers of the Great Lakes would benefit greatly, with Detroit and Chicago finding themselves in a position to compete with Argentina in exporting meat to Europe.

Statewide, the livestock and meat industry was one of Michigan's most important. In 1940 there were 5 million people living in Michigan, and almost 4 million head of livestock on its farms. The per capita consumption of meat for the average Michigander was about 135lbs per year, meaning that there was plenty left over for export. The livestock slaughtered in the local plants like Hammond's were drawn from both greater Michigan and the West, and even Montana shorthorn and mutton stock was shipped here.

I found evidence of yet another fire in 1911, seen in the historic photo above, showing damage to what I believe was this same exact building I was exploring.

Out of the venerable complex that once stood here, this particular structure I was exploring was erected just five years after Upton Sinclair's infamous novel The Jungle was released in 1906, depicting the savage scenes and unsanitary, inhumane working conditions of the great Chicago Union Stock Yards. The Jungle shocked the nation, causing even meat-loving President Teddy Roosevelt to order a federal investigation into the allegations made in the novel (most of which turned out to be horribly accurate). The widespread outrage that the book caused in America led Congress to pass food safety legislation, but the poor labor conditions of slaughterhouse workers remained essentially unchanged.

Another old article I pulled up was from the December 1910 Detroit Free Press, which described a tour of the newly expanded and updated Hammond-Standish plant—including this building. One of the sub-headlines was, "Animals Climb up to Their Executioners," a gleeful exclamation of how wonderfully novel and efficient this place was. Officials bragged that "equipment here was more modern than in the big packing plants of Chicago." Perhaps this was designed to assuage public fears in The Jungle's wake of poor peoples' severed fingers ending up in their breakfast sausage.

There is another series of posts on the atdetroit.net forum by a man who used to work for Hammond-Standish in this building in the late 1950s to early '60s, sharing some of his memories. Just out of high school and working to pay for college, he said that the "money was great, but the work was real tough and dirty." He was also a member of the Amalgamated Meatcutters and Butcher Workmen of America, "and damned proud of it," saying,

I think this room was where the killing was done; it is located at the top of the cattle runway near the back of the plant, closest to the railway. Perhaps these grooves in the floor were for channeling the blood raining from above into a drain system:

In April of 1950 Joseph Strobl, a 33-year-old former cigar company president made news by purchasing Hammond, Standish Co., and immediately set in motion a plan to double the company's output, institute new selling techniques, and get back into large-volume cattle slaughtering. At the time Hammond only dealt in pork, such as sausage and bacon.

An article in LIFE Magazine in November, 1951 however indicated that things were not going well. The company had shut down that August due to being on the losing end of a government squeeze that imposed a ceiling on the products they sold, but not the hogs they bought. Many packers including Hammond-Standish got caught between the low OPS ceiling on pork and the high, uncontrolled price of live hogs. It was forced into receivership after eight straight weeks of heavy losses.

The laborers of the plant, whose paychecks had bounced and whose skills were not in demand elsewhere in the Motor City, decided to form a pact with the company to keep it afloat until things improved. The large part of them had been there for many years and liked working there, and none were eager to start at the bottom of the totem pole at some other company. Their union, CIO Local 190, came up with a plan where the workers would donate up to nine weeks' labor free, and management would give up their salaries, in hopes that it would pull the company out of the red.

The CIO's national leadership thought the gamble was insane, but nonetheless the union local approved the plan by a vote of 235-0. After three weeks, the company was doing well enough to start paying employees again, and the future was looking good. Another subsequent article in the February, 1952 Detroit Free Press said that payroll was still being met, and profits were up.

According to a list of company records held in the Detroit Public Library's Burton Historical Collection, the dissolution of the Hammond-Standish company occurred from 1954 to 1956. That was also the year that the Hammond Building downtown was demolished to make room for the new National Bank of Detroit, marking the closing of a rich chapter of Detroit lore, and the casting of the Hammond name into the dustbin of history.

I suspect that this contraption drove the conveyor belt that moved the cattle from the railroad cars up to be slaughtered here on the killing floor:

One of IBP's biggest and most (in)famous packing plants was built at Greeley, Colorado. I had a friend who lived in nearby LaSalle, and when I visited him I was able to experience the "Greeley Wind," which was an unavoidable stench that enveloped the town, comparable to having one's head stuck inside of a cow's anus. The horrible smell came primarily from the "waste lagoons," vast swamps of urine / feces / blood / etc. from the slaughtered animals. My friend told me that the stench intensified by an order of magnitude on Fridays, when the waste lagoons were "burned off" to supposedly dispose of the vile soup.

I made my way onto the roof. This magnificent panorama was what I had come here for...the Michigan Central Depot looming next to the downtown skyline:

A view of Mexicantown, with the smokestacks of Zug Island behind it:

The Masonic Temple, and the new Pizzarena site:

The casino, that old church on 17th Street, and the CPA Building:

The Roosevelt Warehouse, once part of the Detroit Post Office:

I wandered out back behind the slaughterhouse on my way home...this was the railroad spur area, where the trains originally came up to the building to load / unload livestock or processed meat. The Southwest Detroit Hospital can be seen across the rail yard, which I explored in an older post:

I suspect that train cars once pulled into this bay of the building for delivering coal or ice? It is hard to tell whether this structure is shown on the Sanborn map, but there was a coal elevator shown in this area on the c.1921 map.

What is the future for this ramshackle old historic building? It's hard to say, but evidence of recent repair work I saw inside seems to indicate that someone cares to keep it around for something. The site is still valuable as an industrial location, or, I guess, it could go the usual route of trendy lofts.

However, it seems to be stuck in limbo at the moment. But I would say that the stretch of Vernor between I-96 and the Michigan Central Depot will be an area to watch for new development in the near future, since it is the connector between two thriving areas: Corktown and Mexicantown. Even though that desolate corridor is mostly a ghost town, it has the potential to blossom...if local slumlords relinquish their death grip on these long-vacant properties, that is. I'm not precisely sure who owns it, but I have seen both WE Co. 1991 Inc. and Dennis Kefallinos listed as owners.

Update: In the past year since I wrote this article, the slaughterhouse and several other vacant structures nearby have begun to see renovation work, and Ford Motor Co. has purchased the old Michigan Central Depot, confirming my prediction that this corridor was on the upswing.

There was another recent fire in here back in April, which was captured by a local photographer. Perhaps the ghosts of Hammond-Standish have become restless once more.

References:

Sanborn Maps for Detroit, Vol. 1 Sheets 32 & 33 (1884)

Sanborn Maps for Detroit, Vol. 1 Sheets 40, 52 & 56 (1897)

Sanborn Maps for Detroit, Vol. 1 Sheets 52 & 56 (1921)

The City of Detroit Michigan, 1701-1922, Vol. V, by Clarence M. Burton, p. 5, 655

The History of Wayne County, Vol. II, by Clarence M. Burton, et al, p. 1059-1061, 1100, 1298

The History of Wayne County, Vol. V, by Clarence M. Burton, et al, p. 371, 523, 537

"Plant Blaze Stirs Ghosts," Detroit Free Press, December 5, 1965, p. 3A, 14A

"A Merchant Prince Dead," Detroit Free Press, December 30, 1886, p. 5

"Fire Last Night," Detroit Free Press, May 22, 1883, p. 6

"A Huge Enterprise," Detroit Free Press, December 4, 1886, p. 5

"Ex-Detroiter Joins 'Meat Hall of Fame'," Detroit Free Press, January 31, 1955, p. 7

"Visit Hammond, Standish Plant," Detroit Free Press, December 20, 1910, p. 5

"Sidney B. Dixon Retires," Detroit Free Press, May 31, 1903, p. 12

"Investigate Death of F. Westokovicz," Detroit Free Press, August 22, 1916, p. 7

The Northwestern Reporter, Volumes 165-166, p. 993

"Retail Dept. of Hammond, Standish & Co., Cadillac Square," Detroit Free Press, October 7, 1905, p. 12

The American Railroad Freight Car: From the Wood-Car Era to the Coming of Steel, by John H. White, Jr., p. 129, 270-274

The Commercial Vehicle, Volume 23 (September 1, 1920), p. 72-73

Polk's Michigan State Gazetteer and Business Directory, 1921 p. 504

"Labor Helps Out the Boss," LIFE, November 26, 1951, p. 105-106

"Packing Firm Thrives on Union Pay Gamble," Detroit Free Press, February 5, 1952, p. 1

"Meat Packer May Merge," Detroit Free Press, August 7, 1958, p. 26

"Financier, 33, Heads City's Oldest Packer," Detroit Free Press, April 30, 1950, p. 12A

The Industries of Detroit: Historical, Descriptive, and Statistical, by John William Leonard, p. 86 (1887)

American Odyssey, by Robert Conot, p. 86, 94, 101

All Our Yesterdays, A Brief History of Detroit, by Frank and Arthur Woodford, p. 202, 230

Fast Food Nation, by Eric Schlosser, p. 152

Territories of Profit: Communications, Capitalist Development, and the Innovative Enterprises of G.F. Swift and Dell Computer, by Gary Fields, p. 105

Chicago's Pride: The Stockyards, Packingtown, and Environs in the Nineteenth Century, by Louise Carroll Wade, p. 106-107

https://www.findagrave.com

http://www.thirdworldtraveler.com/Health/Cogs_Machine_FFN.html

http://dplbibdiv.pbworks.com/f/bhc01108.html

https://digitalcollections.detroitpubliclibrary.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A173995

http://www.atdetroit.net/forum/messages/76017/75803.html?1152245604

http://peacockroom.wayne.edu

http://www.midcontinent.org/rollingstock/builders/michigan-peninsular.htm

http://hfha.org/the-ford-story/the-birth-of-ford-motor-company/

https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/hammond-building

https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/hammond-george

https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/davis-william

https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/sets/7139

http://www.calumetcitychamber.com/slide-view/about/

https://www.google.com/patents/US29635

https://www.google.com/patents/US78932

The name George H. Hammond does not readily conjure up mental images of some famous product, like that of Henry Ford, the Dodge Brothers, or even Charles Kettering, but Hammond once commanded an empire that stretched across the breadth of this nation, his name was on the side of almost every train, a large city in Indiana is named after him, and Michigan's first skyscraper was even built in his honor, but today this unremarkable pile of brick here is basically the only thing left to prove this legendary Detroiter ever existed...

George Hammond was a meatpacker. Although he is often credited with inventing refrigerated rail transport, it would be more correct to say that he was the one who pioneered means to make it practical, and who was the one most instrumental in popularizing it. Which is what we Detroiters do—we don't actually invent things—we perfect them, or invent new ways to use them that no one thought of before. You can see this from my 14-point list, above.

This building was once part of a larger complex of buildings that made up the old Hammond, Standish & Co. meatpacking plant. You may recall that I wrote about the meatpacking business in Detroit in an older post, exploring the Thorn Apple Valley Slaughterhouse in Eastern Market.

By the 1920s, this was a robust complex of buildings densely nestled together atop the Michigan Central Railroad's many sidings and spurs that sat behind the big iconic train station between Corktown and Mexicantown. Perusing the many labels that the c.1921 Sanborn map used to identify the buildings that used to stand here, I see "hog coolers," "cattle pens," "dry salt rooms," "cattle runway," "pork curing," "packing & shipping," "hanging," "rendering," "cooper shop," "coal bunkers," "refrigerating & cutting," "ice machines," "freezing tanks," "sausage manufacturing," "wholesale market," "lunch room," "retail market," and "offices."

This particular building is actually two stuck together, labelled Building #9 and #10 on the Sanborn map, built in 1911 and 1916, respectively. The rest of the buildings were also of mixed wood-post and reinforced concrete construction, all of them built before 1918. The newer building was labeled as containing the "lard refining room," "cooper shop," and "beef coolers." The older building was labeled as "fertilizer building," "rendering building," and "abattoir." What is an abattoir, you ask? Well, it's a fancy French word for a place where frightened animals are decapitated and ground into a paste that you will eventually cook and put in your mouth. Perhaps this Jam Handy-style educational film will help explain: "Meat and You"

For five hours "it burned stubbornly in the night, a five-alarm fire that danced elusively, like a ghost through the old abandoned building" on the night of November 27, 1965, a Free Press article recounted, "before 120 firemen put it to rest as it kept hissing in protest before the dawn when ghosts must sleep." That was the night this complex was reduced to the one remaining building you see here. Ironically, the Detroit Historical Museum was also running an exhibit on the life of Mr. Hammond at the time of the fire.

|

| Image from Newspapers.com |

After six months of that he sold it all to come to Detroit at the behest of a friend, in 1854. He then opened a hat and mattress factory here, but after only a few years it was destroyed by fire, leaving him nearly destitute. "Fire appears like a red thread on the fabric of Hammond's story," the Free Press reporter foreshadowed.

The prosperity that came to Detroit following the Civil War (and those who survived it) enabled Hammond to expand his business into a bigger store at 38 Michigan Grand Avenue, which is what Cadillac Square used to be called. Apparently the Civil War had taught him a thing or two about butchery, so he began slaughtering his own cattle here on 20th Street, and sold meat wholesale as well as retail. There was another fire in May 1883, nearly destroying his shop at Cadillac Square & Bates, but he was financially in a much better position to recover by that point.

|

| Image from Newspapers.com |

|

| Image from Burton Historical Collection |

Mr. Davis was a fish merchant who claimed some level of engineering ability and happened to have a market stall next to Hammond's. He had been interested in refrigeration for some time, since he had his fish brought in all the way from Lake Superior, and in fact he'd already designed stationary refrigerators for himself and a couple friends in the fruit business. Hammond provided the financing, and had Davis engineer him a refrigerated boxcar, known to railroaders as "reefer" cars for short. In 1868 Davis was granted U.S. Patent #78932 for his reefer car—and then promptly died that same year. Hammond bought the patent rights from Davis's heirs, and the first Hammond-Davis reefer was built the following April at the Michigan Car Co. Works of Detroit. Hammond risked a shipment of 16,000lbs of beef to Boston, and it arrived there in May 1869, allegedly in a more appealing condition than the beef which—according to the local papers—could be found in Boston's own meat markets. Thus, a new industry was born, driven by a newfound demand.

By the way, I wrote a lot about Michigan's connection to the history of refrigeration technology in other posts on this website:

The "Cathedral of Refrigeration"

Lambs to the Slaughter

How Detroit and the Yoopee Used to be Connected

Acme Jackson

Arctic Ice Cream

Anyway, even though there were primitive reefer cars in service as early as the 1840s, many of them were poorly designed. The first patent ever granted for a refrigerated boxcar was actually issued to a Detroiter named John B. Sutherland, in November 1867, several months before the Hammond-Davis design. Sutherland was the master car builder of the Michigan Central Railroad at the time, and also had an earlier patent regarding sleeper cars. He lived at the corner of 10th & Woodbridge (roughly where West Riverfront Park is today), and was one of the original trustees of the Wayne County Savings Bank.

According to the book All Our Yesterdays, A Brief History of Detroit by Frank and Arthur Woodford, before Detroit became the Motor City it was already well known as a railcar manufacturing center after the Civil War. Even though it was not invented in Detroit, the famous Pullman sleeper car was manufactured here from 1871 to 1893, and along with Sutherland's and Davis's work on the refrigerator car, other innovations in railroading were inspired, including the snow plow and the track cleaner, both invented in Detroit by Augustus Day.

According to the book The American Railroad Freight Car by John H. White, the Hammond-Davis reefer cost $2,000 each to build, leading White to call it "as expensive as it was impractical." It was not successful as a year-round meat carrier he wrote, since in warm weather dressed beef would occasionally arrive spoiled. Also, since the carcasses were suspended from the ceiling of the car they tended to shift when the train entered a curve, causing a few derailments. A fruit dealer named Parker Earle had tried a Hammond-Davis reefer for a shipment of strawberries but found it to yield poor results, since the berries closest to the brine tanks were damaged by frost and could not be sold. Another load of fruit was sent to California in late 1870, with better results. Despite these faults, the Hammond-Davis design was greatly improved in the 1880s, and the cars stayed in use for quite a while longer.

Prior to Davis's design, "refrigerated" railcars were merely boxcars packed with ice blocks—and they required 11 tons of it—making shipping dressed beef unfeasible without constantly re-icing the railcars. However, shipping live animals long-distance was also inefficient because they would lose weight and quality during the trip. Livestock needed to be fed during long trips, and their manure disposed of afterward. But shipping dressed beef as opposed to the whole animal represented a 60% weight reduction—which in turn represented a 60% increase in profits for men like Hammond. The practical reefer car was the key to all these problems—and with Davis's patented brine circulation system, only 2,500lbs of ice was needed. Although the Davis reefer did have its flaws, this was the development Hammond needed to start a revolution in the transport of perishable goods.

The only hangup was the fact that the railroads made their money from shipping more weight, not less, so they balked at Hammond's overtures of building reefer cars to ship dressed meat. Since the big railroads running through Chicago were major shareholders in the great Union Stock Yards there, they were reluctant to do anything that would hurt their own business. The railroads were invested heavily in stockyards, feedlots, and thousands of cattle hauling cars that were not adaptable to any other purpose. Just when they had everything set up perfectly White writes, a group of meatpacking firms led by Hammond "wanted to ruin everything" by shipping dressed beef to the big Eastern cities. Those that united behind Hammond included Swift, Cudahy, and Armour—his main competitors—yet they joined him in his fight against the big railroads.

The railroads responded by doing what came naturally—they raised their rates on shipping dressed meat, and would refuse to supply or run reefer cars. So the Midwestern meatpackers turned to Michigan and the Grand Trunk Railroad, which passed through Canada and was not financially beholden to the Union Stock Yards, and they purchased their own cars. Hammond-Standish already shipped through Canada via the Michigan Central Railroad.

White says that the idea of shipper lines originated with the meatpackers of the Midwest. Hammond originally worked with the Blue Line, but later decided to operate his own line. By 1885 he had 600 reefer cars in service, and by the year 1900 that number had doubled. Other western meatpackers soon saw the potential profit in shipping dressed beef to the population centers of the East Coast, and subsequently Swift, Cudahy, and other big names started their own shipper lines.

There was more than a little resentment of the railroad industry in those days, which was seen by the common man as a corporate juggernaut owned by tycoon monopolists like Vanderbilt and J.P. Morgan, who constantly jacked up rates at will on a captive market. It was this very resentment of the railroad that in large part fed directly into the appeal of the Detroit automobile industry once the Motor City got going building cars. The automobile was advertised as a symbol of freedom—not just freedom from being confined to rails, but freedom from being forced to pay the fat-cat railroad tycoons to use them. It was this same sentiment that led to the dissolution of the Detroit street rail system, but that is another story. Funny how the bran-new Q-Line everyone is suddenly excited about is also controlled by a fat-cat tycoon today (ahem, Dan Gilbert)...okay I'll shut up now.

But the connections between the meatpacking and railroad industries and the Detroit automobile industry go even deeper than that. It is well known that Henry Ford himself took his inspiration for the moving assembly line from the methods used in slaughterhouses. A historic photo at thehenryford.org depicts a conveyor at Swift & Co. in Chicago, moving hog carcasses past the men who did the meat cutting. The photo's caption reads,

To keep Model T production up with demand, Ford engineers borrowed ideas from other industries. Sometime in 1913 they realized that the "disassembly line" principle employed in slaughterhouses could be adapted to building automobiles—on a moving assembly line.Also worth mentioning is the fact that Henry Ford's first job after he left his father's farm in Dearborn was at the Michigan Car Works in 1879—the same year that firm began building Swift & Co.'s first reefer cars. As the legend goes, Henry was fired from there because he angered older employees by doing jobs in 30 minutes that usually took five hours.

Speaking of Gustavus F. Swift, it almost seems as if he got into the dressed beef distribution business specifically to compete against Hammond-Standish, judging by a book about the Chicago Stockyards by Louise Carroll Wade. Like Hammond, Swift originally hailed from Massachusetts, and relocated to Chicago in 1875 where he promptly became the first meatpacker in that city dedicated to shipping dressed beef, like Hammond had been doing in Detroit.

He hired engineer Andrew Chase to design him a reefer that was an improvement over the Hammond-Davis car, but the Michigan Central Railroad refused to build them for him (perhaps out of loyalty to Hammond?). To build his reefers Swift was able to contract with the Michigan Car Co. Works, and later the Peninsular Car Co. (both in Detroit). Hammond claimed patent infringement, but the court ultimately sided with Swift. Mr. Swift also took his business to the Grand Trunk Railroad for running the cars east, because it was a competitor of the Michigan Central—the carrier of his main rival, Hammond-Standish.

He hired engineer Andrew Chase to design him a reefer that was an improvement over the Hammond-Davis car, but the Michigan Central Railroad refused to build them for him (perhaps out of loyalty to Hammond?). To build his reefers Swift was able to contract with the Michigan Car Co. Works, and later the Peninsular Car Co. (both in Detroit). Hammond claimed patent infringement, but the court ultimately sided with Swift. Mr. Swift also took his business to the Grand Trunk Railroad for running the cars east, because it was a competitor of the Michigan Central—the carrier of his main rival, Hammond-Standish.

By 1873 Hammond-Standish was making $1 million per year, and by 1875 it was $2 million. They set up plants and warehouses in Boston, Omaha, Indiana, New York, and even Chicago itself—the heart of "The Jungle." The town of Hammond, named after Mr. Hammond himself, grew to become Indiana's sixth largest city. He even began shipping beef to Europe! According to The History of Wayne County by Clarence M. Burton, Hammond was the first to send reefer cars across the ocean. One article says he invented a refrigeration room for seagoing ships, successfully delivering his first consignment of dressed beef in 1879 to Liverpool, England.

|

| Image from Google Books |

In 1881 Mr. Standish held the post of secretary and treasurer at the G.H. Hammond Co. (a branch of the parent company, I presume), which moved its general offices to Chicago in 1889, and subsequently merged in 1902 with the National Packing Co. (aka, the "Beef Trust," which was broken up by the Supreme Court in 1905). In 1904 he returned to Detroit to become secretary of Hammond-Standish again. A Free Press article in October 1905 indicated that C.F. Hammond, J.D. Standish, S.B. Dixon were all still the executive officers of the company. Burton also lists a Charles Dana Standish, perhaps an older brother, as being a partner in Hammond-Standish, who from 1893 to 1900 also helped establish the J.H. Hammond Co., which was the branch of the company that was based in Indiana on the edge of metropolitan Chicago. The town subsequently named itself Hammond.

Standish Street (which runs in front of this building) was actually named Hammond up until sometime between 1884 and 1897 (according to the Sanborn maps). Why the name was changed I have no idea, but it is interesting to note that the name change might have occurred shortly after the death of George Hammond in 1886...maybe there had been some jealous rivalry between the two business partners?

The c.1884 Sanborn map of Detroit shows the old original complex from the 1860s still standing here (which burned down one year later), and the residential neighborhood in this area was already fully developed. There was a planing mill labeled "Diamond Match Co." across the street from this building, on the corner of 21st where Hammond's truck garages would later sit. Nearby was the Detroit Bridge & Iron Works, Stephen Pratts Boiler Works, various coal and lumber yards, "Williard Clark & Co. Pork Packing" was across the railyard from this building. Also of note in the area, the Detroit Soap Works was shown at the corner of what would later become Vernor and 25th, although in 1884, 25th Street was the city limits. I wonder if they got their tallow from Hammond.

The c.1897 Sanborn map shows the new complex starting to take shape on this site. "Parker, Webb & Co. Pork Packers," and "Caplis & Cross, Beef Slaughterers" were now located just north of the Michigan Central railyard, on 20th Street where Williard Clark & Co. had been on the 1884 map.

By 1886 Hammond was slaughtering 2,000 head of cattle and producing 50,000lbs of oleomargarine per day, and annual sales hit $15 million; they also had distribution warehouses in East Saginaw, Bay City, and Mackinaw. That winter Mr. Hammond suddenly perished of an apparent heart attack at his Victorian mansion at 105 Howard Street. He was only 48 years old...too much cholesterol in his meaty diet I guess. This next photo shows Mr. Hammond's home, which was apparently built on the same site as that first meat shop he ever opened, way back in 1857:

|

| Image from Burton Historical Collection |

Construction on it had been stalled since "the labor troubles last summer," the article noted, but claimed that with the death of its founder the business "was headed for its doom." In 1890 Hammond-Standish was sold to a British company according to the Free Press, later absorbing the Armour Meat Co., but it would seem that at least the Detroit part of the business nonetheless lived on under the Hammond name until the 1950s.

Mr. Hammond left behind his wife Ellen Barry, and eight children, as well as the largest family real estate holdings in Detroit, and an estate worth $5 million. He was described in one article as an "unostentatious" philanthropist, and is enshrined in Detroit's historic Elmwood Cemetery. Of the eight heirs to the Hammond legacy, sons George, Charles, Edward, and daughter Florence went into the family business. Charles F. Hammond became president and treasurer of the meat business, while Edward was president of the Hammond Building Company and Florence served as its secretary and treasurer, according to the Detroit Public Library.

When George Hammond died, he had just begun work on a fabulous new landmark office building downtown. A site had been cleared, but nothing had been built yet. Chicago architect Harry W.J. Edbrooke was able to persuade Mrs. Hammond to hire him to finish the planned skyscraper in her husband's memory.

According to historian Robert Conot, when the Hammond Building opened in 1890 a state holiday was declared, and people came from hundreds of miles around to see the marvelous new tower. Bands played, speeches were made, fireworks were launched, and a tightrope walker awed the crowd by traversing a cable strung from the belltower of Old City Hall to the roof of the new skyscraper. According to detroithistorical.org, it was one of the largest masonry buildings ever constructed in the United States at that time.

|

| Image from Burton Historical Collection |

As an artist in his prime, James McNeill Whistler painted the famously controversial Peacock Room, which was later installed in the landmark Detroit mansion of Charles Lang Freer, at 71 East Ferry Avenue. Mr. Freer was an industrialist and an art patron, who just so happened to have been co-founder of Detroit's Peninsular Car Co., which built the reefer cars that improved on the Hammond-Davis design for Swift & Co.—how's that for six degrees of separation?

For all of their to-do about the railroad, by 1920 Hammond-Standish had almost nothing to do with it, having converted all of its shipping to be done by motor truck instead. Hammond both led the way to, and away from the idea of shipping meat by rail. An article in the trade journal The Commercial Vehicle bragged that Hammond-Standish was able to reach customers 30 miles away without use of the railroads, and furthermore deliveries within that range were completed two or three times quicker than by rail. The article cited high rail freight rates and hub warehousing cold storage costs needed to prevent spoilage during shipment—all of which were eliminated when shipping by motor truck.

When Hammond started out in the 1850s, it was with 40 horses and wagons, limiting sales to local demand. The outside business gained from the increased range of motor truck delivery more than doubled the company's sales.

In 1920 Hammond operated five Ford light delivery trucks, five 2-ton and seven 3.5-ton Federal Motor Trucks, and one 4-ton Packard truck. With the trucks it was possible for one driver to take on two or more routes per day, whereas in the days of horses he could only complete one route per day. This stony-faced, barrel-chested Corktown Irishman was apparently the lug in charge of Hammond's truck fleet in the 1920s:

|

| Image from Google Books |

Polk's City Directory for 1921 shows Hammond-Standish owning several other buildings in the city, at 2424 Riopelle in Eastern Market, at 8504 Jos. Campau in Hamtramck, at 7871 W. Jefferson in Delray, and at the corner of 18th & Perry near Western Market. The 1940 Polk's lists another location at 1549 Division in Eastern Market (now Jimmy's Quality Meats), which is the only one of these buildings still standing today.

On the south side of Standish Street from this building in 1921 were rows and rows of frame houses, a small bowling alley, as well as the Schulte Soap Co. (manufacturers of tallow, according to Sanborn maps). Small wonder they would be located across from a slaughterhouse. At the corner of 21st there was also another smaller ancillary complex of Hammond-owned buildings, labelled as garages for the company's delivery trucks, supply storage, and "hair cleaning works." I presume that this meant Hammond-Standish was also in the business of selling the hair shorn from their cattle, which was being used for upholstery purposes by the Detroit automobile industry at that time.

In the immediate surroundings of this building, other industries that were shown on the c.1921 map included the F.J. Hasty & Sons Cooperage Works next-door (making wooden barrels and casks), and next to them was the Griffin Wheel Co. foundry, makers of car wheels and other chilled castings for the railroad industry.

This was the building that faced the railroad spurs, and had open shipping docks all along its western side for loading the meat onto the trains for shipment. The rails were ripped out long ago, and the docks were converted for truck shipment.

The 1940 Polk's city directory contained a detailed writeup on the Hammond-Standish Co., which was transcribed on the atdetroit.net forum by user "Mikem." The directory said that the Detroit packing industry had suffered from a loss of "the national fame it deserves" due to the overwhelming focus on the city's auto industry, and that when meatpacking is mentioned, cities like Chicago and Kansas City came to mind instead.

Detroit was then estimated to be fourth in the nation for meatpacking business, and was one of the few cities killing enough livestock to provide for its own needs without importing. Detroit was still doing quite a healthy meat export business as well, and Polk's mentioned that when the St. Lawrence Seaway project was completed the meatpackers of the Great Lakes would benefit greatly, with Detroit and Chicago finding themselves in a position to compete with Argentina in exporting meat to Europe.

Statewide, the livestock and meat industry was one of Michigan's most important. In 1940 there were 5 million people living in Michigan, and almost 4 million head of livestock on its farms. The per capita consumption of meat for the average Michigander was about 135lbs per year, meaning that there was plenty left over for export. The livestock slaughtered in the local plants like Hammond's were drawn from both greater Michigan and the West, and even Montana shorthorn and mutton stock was shipped here.

|

| Image from National Automotive History Collection |

Out of the venerable complex that once stood here, this particular structure I was exploring was erected just five years after Upton Sinclair's infamous novel The Jungle was released in 1906, depicting the savage scenes and unsanitary, inhumane working conditions of the great Chicago Union Stock Yards. The Jungle shocked the nation, causing even meat-loving President Teddy Roosevelt to order a federal investigation into the allegations made in the novel (most of which turned out to be horribly accurate). The widespread outrage that the book caused in America led Congress to pass food safety legislation, but the poor labor conditions of slaughterhouse workers remained essentially unchanged.

There is another series of posts on the atdetroit.net forum by a man who used to work for Hammond-Standish in this building in the late 1950s to early '60s, sharing some of his memories. Just out of high school and working to pay for college, he said that the "money was great, but the work was real tough and dirty." He was also a member of the Amalgamated Meatcutters and Butcher Workmen of America, "and damned proud of it," saying,

I worked with some remarkable people there and I think I learned more about the world there than I did at Wayne State. The smell was, at best, pungent. The waste (bones, hooves, etc.) went to Detroit Rendering Co. and those trucks made pungent seem like Chanel #5.

My moniker while working was "collich-boy" because the other guys knew I was working to save for tuition. They were all hard workers and good men and, being young and idealistic, I had to show them that I could work as hard as they did. Dumb, but I sure learned a lot killing beasts and making hot dogs.He worked at both Hammond-Standish and Hygrade's (2811 Michigan Avenue). At Hygrade's, he unloaded reefer cars full of "picnic hams" and regular hams, into processing bins. Notably, he wrote that the meat came to Hygrade's plant via rail from Indianapolis, but at Hammond-Standish everything arrived by truck only.

I think this room was where the killing was done; it is located at the top of the cattle runway near the back of the plant, closest to the railway. Perhaps these grooves in the floor were for channeling the blood raining from above into a drain system:

In April of 1950 Joseph Strobl, a 33-year-old former cigar company president made news by purchasing Hammond, Standish Co., and immediately set in motion a plan to double the company's output, institute new selling techniques, and get back into large-volume cattle slaughtering. At the time Hammond only dealt in pork, such as sausage and bacon.

An article in LIFE Magazine in November, 1951 however indicated that things were not going well. The company had shut down that August due to being on the losing end of a government squeeze that imposed a ceiling on the products they sold, but not the hogs they bought. Many packers including Hammond-Standish got caught between the low OPS ceiling on pork and the high, uncontrolled price of live hogs. It was forced into receivership after eight straight weeks of heavy losses.

The laborers of the plant, whose paychecks had bounced and whose skills were not in demand elsewhere in the Motor City, decided to form a pact with the company to keep it afloat until things improved. The large part of them had been there for many years and liked working there, and none were eager to start at the bottom of the totem pole at some other company. Their union, CIO Local 190, came up with a plan where the workers would donate up to nine weeks' labor free, and management would give up their salaries, in hopes that it would pull the company out of the red.

The CIO's national leadership thought the gamble was insane, but nonetheless the union local approved the plan by a vote of 235-0. After three weeks, the company was doing well enough to start paying employees again, and the future was looking good. Another subsequent article in the February, 1952 Detroit Free Press said that payroll was still being met, and profits were up.

Another follow-up story in the August 1958 Free Press said that Hammond-Standish emerged from voluntary receivership in 1956, but had been fighting an uphill battle ever since 1951, still trapped between government ceilings and uncontrolled live hog prices. Employees took haircuts three times since then in order to help the company stay afloat, but it was apparent that the company would have to enter a merger. Joseph Strobl had resigned as president, but remained a major stockholder.

According to a list of company records held in the Detroit Public Library's Burton Historical Collection, the dissolution of the Hammond-Standish company occurred from 1954 to 1956. That was also the year that the Hammond Building downtown was demolished to make room for the new National Bank of Detroit, marking the closing of a rich chapter of Detroit lore, and the casting of the Hammond name into the dustbin of history.

In the tradition of The Jungle, the contemporary book Fast Food Nation by Eric Schlosser makes some interesting observations about the modern American meatpacking industry. In the old days meatpacking was done in urban areas of the major cities, each of which had a district near a railyard dedicated to meatpacking. Livestock were shipped in from the West by rail, slaughtered in a building like this, and sold to local butchers and wholesalers.

In 1960, two former Swift & Co. executives decided to change this model and formed their own company, Iowa Beef Packers (IBP), to compete with the old industry goliaths (although by that time Hammond-Standish had already fallen).

In 1960, two former Swift & Co. executives decided to change this model and formed their own company, Iowa Beef Packers (IBP), to compete with the old industry goliaths (although by that time Hammond-Standish had already fallen).

IBP built their slaughterhouses out in the country on the same sites where the cattle were being raised, far from the urban centers. This allowed them to escape the influence of the labor unions of the big cities, while also more easily exploiting the cheap labor pool of "illegal immigrants" and migrant workers in the West. The new Interstate Highway system allowed all shipping to be done by truck, completely cutting the railroads out of the picture and letting taxpayers fund the maintenance of their transportation infrastructure.

Schlosser writes,

The new IBP plant was a one-story structure with a disassembly line. Each worker stood in one spot along the line, performing the same simple task over and over again, making the same knife cut thousands of times during an eight-hour shift. The gains that meatpacking workers had made since the days of The Jungle stood in the way of IBP's new system, whose success depended upon access to a cheap and powerless workforce."We've tried to take the skill out of every step," A.D. Anderson bragged. Just like the new McDonald's restaurant chain, it eliminated the need for skilled workers, which also meant not having to pay them as much. 'Murica! This represented the dawn of the "fast food" era.

One of IBP's biggest and most (in)famous packing plants was built at Greeley, Colorado. I had a friend who lived in nearby LaSalle, and when I visited him I was able to experience the "Greeley Wind," which was an unavoidable stench that enveloped the town, comparable to having one's head stuck inside of a cow's anus. The horrible smell came primarily from the "waste lagoons," vast swamps of urine / feces / blood / etc. from the slaughtered animals. My friend told me that the stench intensified by an order of magnitude on Fridays, when the waste lagoons were "burned off" to supposedly dispose of the vile soup.

Roosevelt Park, and Michigan Central Depot:

The Masonic Temple, and the new Pizzarena site:

The casino, that old church on 17th Street, and the CPA Building:

The Roosevelt Warehouse, once part of the Detroit Post Office:

I wandered out back behind the slaughterhouse on my way home...this was the railroad spur area, where the trains originally came up to the building to load / unload livestock or processed meat. The Southwest Detroit Hospital can be seen across the rail yard, which I explored in an older post:

I suspect that train cars once pulled into this bay of the building for delivering coal or ice? It is hard to tell whether this structure is shown on the Sanborn map, but there was a coal elevator shown in this area on the c.1921 map.

However, it seems to be stuck in limbo at the moment. But I would say that the stretch of Vernor between I-96 and the Michigan Central Depot will be an area to watch for new development in the near future, since it is the connector between two thriving areas: Corktown and Mexicantown. Even though that desolate corridor is mostly a ghost town, it has the potential to blossom...if local slumlords relinquish their death grip on these long-vacant properties, that is. I'm not precisely sure who owns it, but I have seen both WE Co. 1991 Inc. and Dennis Kefallinos listed as owners.

Update: In the past year since I wrote this article, the slaughterhouse and several other vacant structures nearby have begun to see renovation work, and Ford Motor Co. has purchased the old Michigan Central Depot, confirming my prediction that this corridor was on the upswing.

There was another recent fire in here back in April, which was captured by a local photographer. Perhaps the ghosts of Hammond-Standish have become restless once more.

References:

Sanborn Maps for Detroit, Vol. 1 Sheets 32 & 33 (1884)

Sanborn Maps for Detroit, Vol. 1 Sheets 40, 52 & 56 (1897)

Sanborn Maps for Detroit, Vol. 1 Sheets 52 & 56 (1921)

The City of Detroit Michigan, 1701-1922, Vol. V, by Clarence M. Burton, p. 5, 655

The History of Wayne County, Vol. II, by Clarence M. Burton, et al, p. 1059-1061, 1100, 1298

The History of Wayne County, Vol. V, by Clarence M. Burton, et al, p. 371, 523, 537

"Plant Blaze Stirs Ghosts," Detroit Free Press, December 5, 1965, p. 3A, 14A

"A Merchant Prince Dead," Detroit Free Press, December 30, 1886, p. 5

"Fire Last Night," Detroit Free Press, May 22, 1883, p. 6

"A Huge Enterprise," Detroit Free Press, December 4, 1886, p. 5

"Ex-Detroiter Joins 'Meat Hall of Fame'," Detroit Free Press, January 31, 1955, p. 7

"Visit Hammond, Standish Plant," Detroit Free Press, December 20, 1910, p. 5

"Sidney B. Dixon Retires," Detroit Free Press, May 31, 1903, p. 12

"Investigate Death of F. Westokovicz," Detroit Free Press, August 22, 1916, p. 7

The Northwestern Reporter, Volumes 165-166, p. 993

"Retail Dept. of Hammond, Standish & Co., Cadillac Square," Detroit Free Press, October 7, 1905, p. 12

The American Railroad Freight Car: From the Wood-Car Era to the Coming of Steel, by John H. White, Jr., p. 129, 270-274

The Commercial Vehicle, Volume 23 (September 1, 1920), p. 72-73

Polk's Michigan State Gazetteer and Business Directory, 1921 p. 504

"Labor Helps Out the Boss," LIFE, November 26, 1951, p. 105-106

"Packing Firm Thrives on Union Pay Gamble," Detroit Free Press, February 5, 1952, p. 1

"Meat Packer May Merge," Detroit Free Press, August 7, 1958, p. 26

"Financier, 33, Heads City's Oldest Packer," Detroit Free Press, April 30, 1950, p. 12A

The Industries of Detroit: Historical, Descriptive, and Statistical, by John William Leonard, p. 86 (1887)

American Odyssey, by Robert Conot, p. 86, 94, 101

All Our Yesterdays, A Brief History of Detroit, by Frank and Arthur Woodford, p. 202, 230

Fast Food Nation, by Eric Schlosser, p. 152

Territories of Profit: Communications, Capitalist Development, and the Innovative Enterprises of G.F. Swift and Dell Computer, by Gary Fields, p. 105

Chicago's Pride: The Stockyards, Packingtown, and Environs in the Nineteenth Century, by Louise Carroll Wade, p. 106-107

https://www.findagrave.com

http://www.thirdworldtraveler.com/Health/Cogs_Machine_FFN.html

http://dplbibdiv.pbworks.com/f/bhc01108.html

https://digitalcollections.detroitpubliclibrary.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A173995

http://www.atdetroit.net/forum/messages/76017/75803.html?1152245604

http://peacockroom.wayne.edu

http://www.midcontinent.org/rollingstock/builders/michigan-peninsular.htm

http://hfha.org/the-ford-story/the-birth-of-ford-motor-company/

https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/hammond-building

https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/hammond-george

https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/davis-william

https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/sets/7139

http://www.calumetcitychamber.com/slide-view/about/

https://www.google.com/patents/US29635

https://www.google.com/patents/US78932

North of the Hammond-Standish property, the long-trackless swath of railroad right-of-way, located south of Canadian Pacific Railway's double-track mainline, is 90 feet wide. ALL of the railroad sidings that once served companies located south of the tracks, between Michigan Central Depot and West Detroit Junction, are long-gone. There are NO railroad grade crossings enroute.

ReplyDeleteI hope this unused, elevated and vacant strip might become something more tangible than a trail-with-rails. I envision a high-speed-rail (HSR) connection, running between Ford Motor Company's renovated depot and Detroit Metro Airport (DTW).