I noticed with some chagrin that there was a superfluously-added street sign on this corner denoting that this stretch of Taylor Street was now called "M.B. Terrell Drive" between Woodrow Wilson and the Lodge Freeway. Little did I know, that name change had everything to do with this vacant house of worship that I was about to explore, and nothing to do with vain politicians renaming things after themselves or their buddies.

Despite a crucifix-shaped sign on the corner of the building that said "Tried Stone Baptist Church," I had no idea what the original historical name of the building was, so as usual I started by consulting the Sanborn maps. The c.1925 Sanborn map shows this structure, labelled as "First Emanuel Congregation." Since the cornerstone on the building says 1924, it had just been built when that map was drawn. On the 1915 Sanborn map this location was a mere couple blocks away from the city limits with the former Greenfield Township, and most of the surrounding lots were still empty.

If you look close at the facade of the building you can see the faint outline of a menorah and the two tablets of the Ten Commandments—traditional Jewish symbols—have been scrubbed from the stone in order to make it look less like a synagogue and more like a Christian church. It was designed by architect Robert Finn.

The book Jewish Detroit by Irwin J. Cohen calls this synagogue "Congregation Beth Tefilo Emanuel," and in the course of my cursory research I have not yet seen it referred to as First Emanuel Congregation anywhere else except the Sanborn map. It does however have the typical Jewish nickname of "Taylor Shul," which just means that it is the synagogue or "school" that is located on Taylor Street. As the literal translation of shul suggests, it also housed an afternoon Hebrew school, and was the largest shul in Detroit's west-side stetl (Jewish neighborhood).

If it had been located on 24th Street, I suppose it would have been named "24th Shul"? There is also a Hooker Street in Detroit, but there are no shuls on it that I know of.

Beth Yehudah (Pingree Shul) was located just a few blocks south of here, and Beth David and Beth Abraham were also in the immediate area. Blaine Shul, which I have written about before on this website, was over at Blaine Street near Linwood.

According to shtetlhood.com, this synagogue merged with another one and subsequently became known thereafter as Beth Tefilo Emanuel Tikva. I imagine that as the Jewish migration out of Detroit's west side up to Oakland County started taking effect, many of these numerous little shuls either moved north or closed entirely. Or they may have had half of their members decide to stay, forcing them to merge with other small shuls in order to stay alive.

Taylor Shul did its fair share of moving as well, and after vacating its original home here in the early 1960s, they briefly had a storefront location at Wyoming & Thatcher near Mumford High, according to the book Echoes of Detroit's Jewish Communities (also by Irwin J. Cohen). Today they are located in the suburb of Southfield at 24225 Greenfield Road.

Meanwhile, Marion B. Terrell, Sr. attended Campbell College in Jackson, Mississippi and began ministering in 1939...you may recognize his name from the street sign that I mentioned earlier. Terrell came up to Detroit in 1945, where he was "called to the pastorate of Tried Stone Baptist Church" in 1949, and remained steadfastly at the head of his congregation for about 50 years.

Tried Stone originated under Rev. Terrell's pastorship in a storefront on Russell Street at E. Kirby, and it moved into this building in the early 1960s, which, as I said was when the sizable Jewish population of Detroit's west side was moving out.

Tried Stone was noted in a 1972 Detroit Free Press article as being very youth-centric (a theme that seems to have continued well into the 1990s, based on another ad for a youth bible conference that I saw in the paper). The Tried Stone Baptist was one of about 40 churches in Detroit that broadcasted services live from their own auditoriums on Sundays, on WGFR.

Legendary boxer Mohammed Ali and legendary stuntman Evel Knievel were in the Detroit area in May of 1987 for a K-Mart shareholders' meeting, according to another article in the Free Press. They decided to put in some community service time and promotional appearances while they were in town as well, which included visiting prisoners at Wayne County Jail and giving out food to the needy at Tried Stone Baptist.

In 1997, for the 30th anniversary of the 1967 Riot, Tried Stone Baptist focused their annual leadership conference on discussing and taking lessons from the tragic insurrection. Conference speakers were to include U.S. Rep. Carolyn Cheeks-Kilpatrick, and Martin Luther King III—the son of the famous civil rights leader—who is a leader in his own right. Another Free Press article tells how local politician Sharon McPhail made an appearance on the pulpit here when she was campaigning to unseat Ed McNamara as Wayne County Executive in 1998.

With the 50th anniversary of that horrific week already close at hand, I look around and see Metro-Detroiters still asking whether we have learned anything from the Riot, or whether anything actually changed.

When the nightmarish 1967 Riot started, it began at a building at the corner of 12th and Clairmount, which was literally only one block to the west of this former synagogue. I imagine these large bright windows to have been dimmed by the thick black smoke drifting through the neighborhood from the fires raging as 12th Street burned.

Judging by the many vacant lots where surrounding houses used to be, I'd say that a fair number of them may have been consumed in the fires as well, but thankfully this building itself survived and is still in fair shape overall, but the start of serious decay from neglect is quite evident:

Again, the Jewish congregation had already moved on a few years before the Riot took place, and this building had already been home to the Tried Stone Baptist congregation for some time.

In the immediate aftermath of the Riot's chaos, Tried Stone was designated as one of the 33 official food distribution centers set up by Mayor Cavanagh's Committee for Emergency Food and Housing Allocation, and it was one of eight that were listed in a July 30, 1967 Free Press article as staying open longer than the rest.

By the mid-1990s, this had already been a traditionally under-served area for quite some time. Rev. Richard P. Wilson saw more than 100 of Tried Stone's 1,200 poor or elderly members die in one year due to preventable illnesses that were going undiagnosed, and decided something had to be done. Wilson enlisted the help of University of Michigan, Wayne State, and the Kellogg Foundation to start up its own primary health care clinic (I assume this explained the modern, white addition to the righthand side of the old synagogue seen in the first photo).

The health center was staffed by Wayne State nursing students and accepted patients with insurance, and charged those without it according to their income level. Rev. Wilson hoped that by offering health care at affordable rates, it would help locals stay well and hopefully stop dying of illnesses that are supposed to be easily cured.

Of all the funerals conducted in this sanctuary, perhaps the most notable was that of Motown star Paul Williams, one of the original five Temptations, and the "soul of the group," according to founder Otis Williams. Paul did most of the group's choreography and sang lead on several of their hit numbers, such as "Don't Look Back."

Sadly Williams struggled with alcoholism and was finally found in his car at 14th & West Grand Boulevard after having apparently committed suicide with a gunshot to the head. His funeral was held here on August 25th, 1973, during which the other Temptations members sang and served as pallbearers. There are still rumors that Williams' death was a murder cover-up and not suicide, but nothing else has ever been proven.

It was kind of surprising to find what looked to be an original chandelier still hanging in here:

Another original-looking chandelier:

A footnote from a scholarly paper by Deidre Lyniece Wheaton notes that Dr. Bill Cosby visited Tried Stone as recently as 2007 to lead a town hall-style discussion to a capacity crowd after his book Come On People was released. The book was about "personal responsibility, a commitment to education, and building stronger families," and it was seen by many as an extension of some of his other controversial opinions on black issues. (Of course, this was well before the entire world came to the consensus that Dr. Cosby was a rapist bastard).

As you can see, the artwork adorning the walls of this sanctuary has taken a turn toward the Baptist since its Hebrew days:

Its townhall shape helps it double as a great community-forum type of structure for non-religious meetings as well. Originally, as an orthodox Jewish synagogue, the balcony would be reserved for women while the main floor seating was for men. In the center of the room would have been the bimah, a raised platform where the scrolls would be carried and prayers recited by the rabbi, according to reader William Frank (I was raised Catholic, so I don't intuitively know these things).

I guess stained glass was never quite in the budget for Beth Tefilo Emanuel or Tried Stone Baptist, so a few colored panes of glass help lend some warmth to this cold dreary Detroit day.

Here is an old 1920s pendant-style light fixture still perfectly intact in the stairwell:

As of 2016 some renovation work is underway on this old building, and at time of writing all new windows have been installed. I would assume that the plan is to make it some kind of a church again.

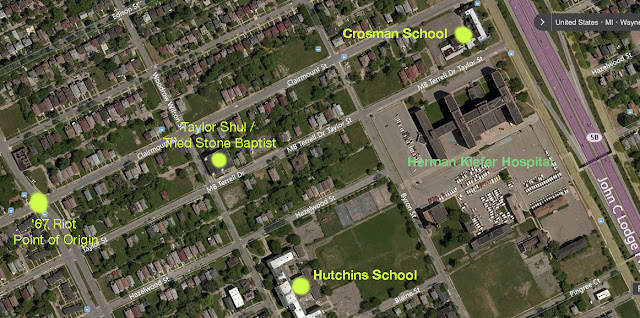

Just for reference, I marked up the following aerial photo taken from Bing.com to show the disposition of this church and the other culturally important buildings/sites in this neighborhood of Virginia Park that I have posted about, such as the Crosman School and Hutchins School:

|

| Image from Bing.com |

References:

Sanborn Maps for Detroit, Vol. 9, Sheet 45 (1925)

Sanborn Maps for Detroit, Vol. 9, Sheet 87 (1915)

Harmony & Dissonance: Voices of Jewish Identity in Detroit, 1914-1967, by Sidney M. Bolkosky, p. 98

Jewish Detroit, by Irwin J. Cohen, p. 93-94

Echoes of Detroit's Jewish Communities: A History, by Irwin J. Cohen, p. 281

"Anniversary Commemoration," Detroit Free Press, July 20, 1997, p. 55

"Why the Sunday Radio-TV Church Fade-out?" Detroit Free Press, February 5, 1972, p. 21

"With Help, Church Opens Health Clinic," Detroit Free Press, November 9, 1998, p. 62

"Jail Inmates get a Surprise Visit from the Champ," Detroit Free Press, May 26, 1987, p. 3

"16 Food Centers Kept Open," Detroit Free Press, July 30, 1967, p. 6

"A Message of Accountability," Detroit Free Press, July 30, 1998, p. 82

Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons (Third Edition), by Scott Wilson, p. 813

Seeking Salvation: Black Messianism, Racial Formation, and Christian Thought in Late Twentieth Century Black Cultural Texts, by Deidre Lyniece Wheaton, p. 165

Journal of the Senate of the State of Michigan, Vol. 1, 1980, by J.S. Bagg, p. 20

http://www.detroitjewishdirectory.com/listing/cong-beth-tefilo-emanuel-tikvah/

http://newgreatertriedstonembc.weebly.com

http://www.shtetlhood.com/Beth_Emmanuel.htm

http://www.angelfire.com/stars/classictemptations/Paulmemorial.html